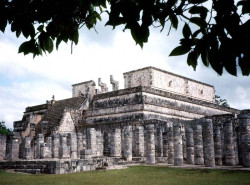

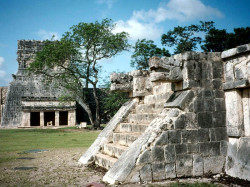

Chichen-Itzá in Mexico

The Mayan Pre-Columbia Site of Chichen-Itzá

Chichén Itzá was a large pre-Columbian city built by the Maya people of the Yucatán State of Mexico. Chichén Itzá was a major focal point in the Northern Maya Lowlands from the Late Classic (AD 600–900) through the Terminal Classic (AD 800–900) and into the early portion of the Postclassic period (AD 900–1200). The site exhibits a multitude of architectural styles, reminiscent of styles seen in central Mexico and of the Puuc and Chenes styles of the Northern Maya lowlands. The presence of central Mexican styles was once thought to have been representative of direct migration or even conquest from central Mexico, but most contemporary interpretations view the presence of these non-Maya styles more as the result of cultural diffusion.

Chichén Itzá was one of the largest Maya cities and was likely to have been one of the mythical great cities referred to in later Mesoamerican literature. The city may have had the most diverse population in the Maya world, a factor that could have contributed to the variety of architectural styles at the site.

As one of the most visited archeological sites in Mexico with over 2.6 million tourists in 2017, the ruins of Chichén Itzá are federal property, and the site is maintained by Mexico's Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia. The land under the monuments had been privately owned until 29 March 2010, when it was purchased by the state of Yucatán.

The Maya name "Chichén Itzá" means "At the mouth of the well of the Itza." Itzá is the name of an ethnic group that gained political and economic dominance of the northern peninsula. The layout of Chichén Itzá site's core developed during its earlier phase of occupation, between 750 and 900 AD. Its final layout was developed after 900 AD, and the 10th century saw the rise of the city as a regional capital controlling the area from central Yucatán to the north coast, with its power extending down the east and west coasts of the peninsula. The earliest hieroglyphic date discovered at Chichen Itza is equivalent to 832 AD, while the last known date was recorded in the Osario temple in 998.

Chichén Itzá is located in the eastern portion of Yucatán state in Mexico. The northern Yucatán Peninsula is karst, and the interior rivers all run underground. There are four visible, natural sinkholes at the site, called cenotes, that could have provided plentiful water year-round at Chichen Itzá, making it attractive for settlement. Of these cenotes, the "Cenote Sagrado" or "Sacred Cenote", is the most famous. In 2015, scientists determined that there is a hidden cenote under the Temple of Kukulkan, which has never been seen by archeologists.

According to post-Conquest sources, pre-Columbian Maya sacrificed objects and human beings into the cenote as a form of worship to the Maya rain god Chaac. Edward Herbert Thompson dredged the Cenote Sagrado from 1904 to 1910 and recovered artifacts of gold, jade, pottery and incense, as well as human remains. A study of human remains taken from the Cenote Sagrado found that they had wounds consistent with human sacrifice.

Between 900 and 1050 AD, Chichén Itzá expanded to become a powerful regional capital controlling north and central Yucatán. Establishing Isla Cerritos on the north coast as a trading port, Chichén Itzá was able to obtain locally unavailable resources from distant areas such as obsidian from central Mexico and gold from southern Central America. The ascension of Chichén Itzá roughly correlates with the decline and fragmentation of the major centers of the southern Maya lowlands as the cities of Yaxuna (to the south) and Coba (to the east) were suffering decline. These two cities had been mutual allies, with Yaxuna dependent upon Coba. At some point in the 10th century, Coba lost a significant portion of its territory, isolating Yaxuna, and Chichén Itzá may have directly contributed to the collapse of both cities.

According to some colonial Mayan sources (e.g., the Book of Chilam Balam of Chumayel), Hunac Ceel, the ruler of Mayapan, conquered Chichén Itzá in the 13th century. Hunac Ceel supposedly prophesied his own rise to power. According to custom at the time, individuals thrown into the Cenote Sagrado were believed to have the power of prophecy if they survived. During one such ceremony, the chronicles state, there were no survivors, so Hunac Ceel leaped into the Cenote Sagrado, and when removed, prophesied his own ascension. However, archeological data now indicates that Chichen Itza declined as a regional center by 1100 AD, before the rise of Mayapan. Ongoing research at the site of Mayapan may help resolve this chronological conundrum.

After Chichén Itzá elite activities ceased, the city may not have been abandoned. When the Spanish arrived, they found a thriving local population, although it is not clear if these Maya were living in Chichén Itzá proper, or a nearby settlement. The relatively high population density in the region was a factor in the conquistadors' decision to locate a capital there. According to post-Conquest sources, both Spanish and Maya, the Cenote Sagrado remained a place of pilgrimage.

Spanish conquest

In 1526, Spanish Conquistador Francisco de Montejo successfully petitioned the King of Spain for a charter to conquer Yucatán. His first campaign in 1527, which covered much of the Yucatán Peninsula, decimated his forces but ended with the establishment of a small fort at Xaman Haʼ, south of what is today Cancún. Montejo returned to Yucatán in 1531 with reinforcements and established his main base at Campeche on the west coast. He sent his son, Francisco Montejo The Younger, in late 1532 to conquer the interior of the Yucatán Peninsula from the north. The objective from the beginning was to go to Chichén Itzá and establish a capital.

Montejo the Younger eventually arrived at Chichén Itzá, which he renamed Ciudad Real. At first, he encountered no resistance and set about dividing the lands around the city and awarding them to his soldiers. The Maya became more hostile over time, and eventually, they laid siege to the Spanish, cutting off their supply line to the coast, and forcing them to barricade themselves among the ruins of the ancient city. Months passed, but no reinforcements arrived. Montejo the Younger attempted an all-out assault against the Mayans and lost 150 of his remaining troops. He was forced to abandon Chichén Itzá in 1534 under cover of darkness. By 1535, all Spanish had been driven from the Yucatán Peninsula.

Montejo eventually returned to Yucatán and, by recruiting Maya from Campeche and Champoton, built a large Indio-Spanish army and conquered the peninsula. The Spanish crown later issued a land grant that included Chichén Itzá and by 1588 it was a working cattle ranch.

In 1894 the United States Consul to Yucatán, Edward Herbert Thompson, purchased the Hacienda Chichén, which included the ruins of Chichen Itza, and received a constant stream of visitors. For 30 years, Thompson explored the ancient city, where he recovered artifacts of gold, copper, and carved jade, as well as pre-Columbian Maya cloth and wooden weapons. Thompson shipped the bulk of the artifacts to the Peabody Museum at Harvard University.

In 1913, the Carnegie Institution committed to conducting long-term archeological research at Chichen Itza, but the Mexican Revolution and the following government instability, as well as World War I, delayed the project by a decade. Then in 1923, the Mexican government awarded the Carnegie Institution a 10-year permit (later extended another 10 years) to allow U.S. archeologists to conduct extensive excavation and restoration of Chichen Itza.

In 1926, the Mexican government charged Edward Thompson with theft, claiming he stole the artifacts from the Cenote Sagrado and smuggled them out of the country. The government seized the Hacienda Chichén. Thompson, who was in the United States at the time, never returned to Yucatán. He wrote about his research and investigations of the Maya culture in a book People of the Serpent published in 1932. He died in New Jersey in 1935. In 1944 the Mexican Supreme Court ruled that Thompson had broken no laws and returned Chichén Itzá to his heirs, which was purchased by Barbachano Peon that same year.

More recently, INAH, which manages the site, has closed a number of monuments to public access. While visitors can walk around them, they can no longer climb them or go inside their chambers. Climbing access to El Castillo was closed after a San Diego, California, woman fell to her death in 2006.

Photographed in 1996